An evening. Or maybe just a night, let me say. Still summer. We can hear the voices through the screens. It is raining out there, in one of them. Then, almost like a prologue for the talk, Omar is talking about his experience as an artist.

Una tarde. O una noche, mejor dicho. Aún es verano. Se escuchan las voces digitales a través de la pantalla. Afuera se escucha la lluvia de un lado. Luego, casi como si esa fuera la introducción para la charla, Omar nos cuenta su experiencia cómo artista.

Gerardo: Qué onda, Omar. Debo decirte que conocimos tu obra por la publicación de Obras Comentadas. La de parodia al FONCA. Pero, bueno, no hablemos de eso. ¿Cómo andas, Omar?

Omar: Bien, bastante bien, con un poco de trabajo, pero tranquilo. Así que bien, disfrutando que por fin hay lluvias.

Uriel: ¿No había llovido allá en Oaxaca?

Omar: No. Ha llovido en los últimos días, pero después de la ola de calor sí fue muy pesado. Bueno, ya refresca un poco, es lo bueno.

Uriel: ¿Sabes? Me pareció a mí muy interesante tu trabajo porque creo que revela una postura política muy ahí. Creo que está implícita, digo, pero que… Yo leo últimamente en el contexto del arte no está tan presente. Veo en el contexto del arte sólo como una especie de virtud egoísta. Quería platicar de eso y quería preguntarte también qué onda con esa idea, ¿cómo surge? O si es muy tuya esta voluntad política que tú tienes.

Omar: Bueno, mi trabajo desde esas fechas hasta ahorita, incluso ahorita más… He intentado que se caracterice por tener un posicionamiento político. Esa es como una de mis intenciones como productor artístico, pero tratando de usar la ironía y la burla hacia mi mismo o hacia otras cosas como herramienta para construir mis proyectos. En este caso, en el 2017 me dieron la beca de Jóvenes Creadores del FONCA y ahí, pues, tenía un proyecto que tenía que ver con la ficción, con la idea de poner en cuestión la figura del artista porque… Estaba imaginando, construyendo la idea, de qué pasaría con un artista que viniera a hacer una intervención pública aquí en Oaxaca, imaginando que es otro artista que tiene ciertas características. Como un artista minimalista. Y presentaba los proyectos, los bocetos. Pero, al mismo tiempo, pues, gran parte de la discusión previa a obtener la beca del FONCA, hubo varios amigos que previamente a mi habían obtenido esa beca, y yo siempre decía: «ah, bueno, ahora eres un artista del Estado» de manera burlona.

Gerardo: Ya.

Omar: Y yo necesitaba dinero, como siempre, y pues cuando me la dieron a mi dije: «ah, es un buen momento, yo que tanto le decía esto a mis amigos». Justo… Estaba en ese momento Peña Nieto en la presidencia y dije: «me voy a adjudicar la idea de que yo soy un artista del Estado». Y a partir de eso fue que fui generando esta idea de construir esta idea de partido político que beneficia o que actúa a favor de los artistas, y así poner en cuestión esa idea, ¿no? Por ejemplo, yo he visto mucho que muchos amigos a compañeros y colegas, cuando obtienen una beca del Estado, dicen: «no, yo me sigo manteniendo crítico al sistema», pero siguen viviendo del sistema. Y dices, bueno, es válido, pero también es cuestionable el hecho de que pareciera que no pasa nada cuando obtiene uno la beca.

Gerardo: What’s up, Omar? I must say we watched your work because of the post of Obras Comentadas. The post about FONCA’s parody, you know? I dunno. But, we won’t talk about it. Let me say: how are you?

Omar: I’m great! Very great. With some work but calm. So, fine, just enjoy the rain.

Uriel: Hadn’t it been raining there?

Omar: No. Well, it’s been raining the last few days, but after the warm season here… It was very deep. I mean, it is fresh now and it’s good.

Uriel: Your work seems very interesting to me, you know? Because I think it reveals a political position intrinsically. I mean, it is implicit, I think, but I read on that any context that doesn’t exist around art lastly. I think art is selfish. Not about social matters, but specifically around the artist’s troubles. I wanna talk about it and I would ask you what about that, how it started. I want to know if that idea is based on a political will you have.

Omar: My work… Since that dates to now… I tried to have a work which can be identified by its political will. It’s like one of my intentions as artistic producer, but just using irony and joking to myself or to whatever that is forming my own projects. In this case, in 2017 I gained a FONCA scholarship and, so, I had a project that was about fiction, with the idea of questioning the artist as a figure… I was imagining, forming the idea: what happens if an artist comes here to make a public installation, thinking he is foreign, and with other characteristics like a minimal artist, I guess. And what happens if he shows us his projects, the sketches and drawings. But, at the same time, it’s about a previous chat with my friends. They used to tell me like: “now you’re a regime’s artist”, as a joke.

Gerardo: I’d see…

G: Una compleja contradicción, ¿no?

O: Si, y pues en mi caso, obviamente no iba a rehusar el dinero porque al final es necesario para jóvenes, o para los que producimos y no tenemos dinero a través de galerías comerciales, a través de mecenas, a través de… Pues, es un ingreso importante para nosotros. Así que, en ese caso, pues, dije, bueno: «continuo con esta burla, en este caso, hacia mi», pero para poner en cuestión cuál ha sido esta relación tensa entre el Estado y los artistas. Ese era… En ese momento como un interés muy genuino que tenía y que sigo teniendo hasta ahora. Por ejemplo, dentro de las reglas de Jóvenes Creadores decía que en cualquier producción audiovisual o impresión, publicación de un libro debía aparecer la leyenda de «Este proyecto fue apoyado por la beca Jóvenes Creadores». Siempre tenía que aparecer. Y dije: «ok, lo tengo que poner». A la vez de poner eso, ponía el logo del local donde trabaja mi mamá, un puesto dentro del mercado, que se llama «Perfumería La Rosa» y lo ponía al lado del símbolo del partido que inventé hace años. Como de alguna manera, ya no tan directo, burlándome de la relación entre el Estado y los artistas, siendo un poco más sutil, siento yo.

G: Está muy cabrón cómo elaboras todo, este concepto, porque no queda nada más en esa burla que le haces a tus amigos. O sea, me parece muy interesante cómo de pronto pasó de un chiste, así como entre compas, a ya presentarlo como, no sé si como una pieza, pero sí un concepto potente. Eso me parece bien interesante porque requiere mucho tiempo y mucho compromiso para poder llevarlo a cabo. Independientemente de que sea una ironía, creo que sí requiere cierto esfuerzo.

O: Sí. Sentí que era importante porque obviamente era como decir: «bueno, yo caí en esto y tan fácilmente como muchos otra gente hacía, hacemos o hacen; que, al obtener la beca, por ejemplo, o cualquier apoyo, en automático cambian el discurso. De decir que no. Antes pensaban que esas becas siempre están coaccionadas. «Siempre se la dan a los mismos, son para los mismos de siempre, es para una élite». Se las dan y claro que es cuestionable. Todas estas relaciones entre el Estado y cómo coaccionan a través de las becas o de los subsidios; claro que se debe cuestionar.

U: Veo a ti te provoca mucha risa hablar de esto, incluso cuando está todo este discurso, que te provocaba risa, te estaba entusiasmando. A nosotros también nos llamó la atención de una manera positiva, pero, ¿has tenido alguna reacción negativa a partir de lo que hiciste?

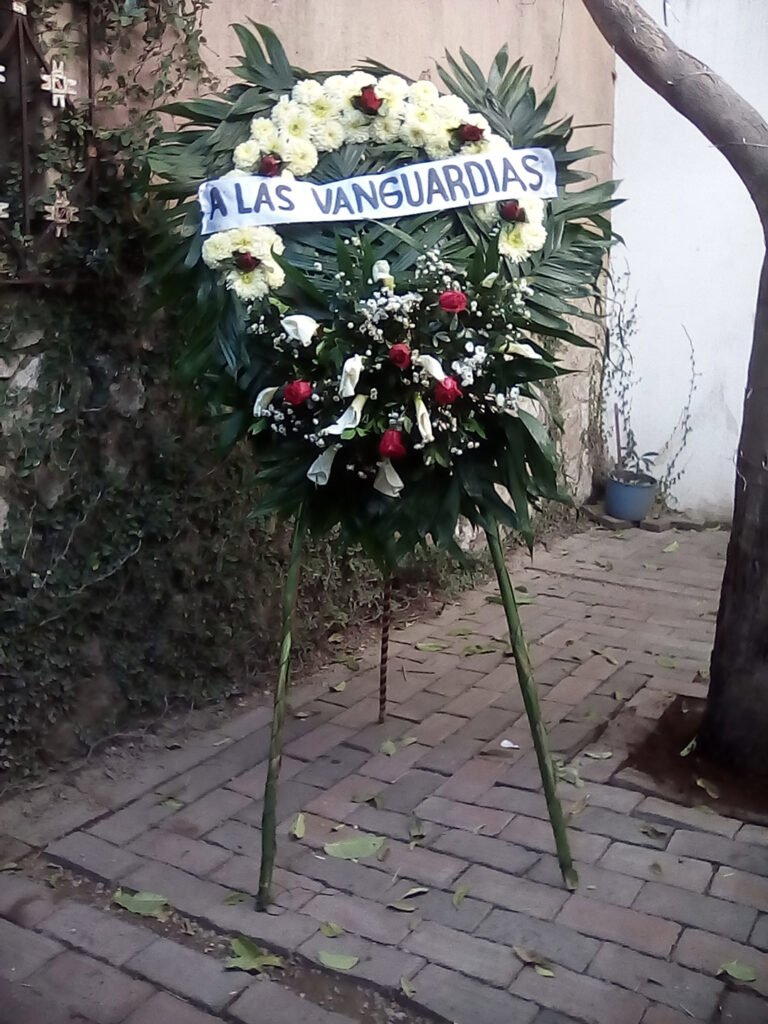

O: Yo sé que a varios amigos no les interesa, o no les gusta porque es muy confrontativo, como muy abiertamente no-polémico. Creo que algo de lo que me estoy dando cuenta es como que siempre he estado pensando en qué es aquello que denominamos artista del siglo XXI: ¿cuáles son sus implicaciones dentro del entramado social? Por ejemplo, tengo una pieza que se llama… Que es algo así como una especie de… Mira es un cartel que dice «NO PASARÁN» que es una frase muy famosa dentro de la guerra civil española, pero algo parecido es una que hice que se llama Los Artistas Son Agentes Inmobiliarios, que tiene que ver con este proceso de gentrificación en la ciudad de Oaxaca y cómo los artistas somos partícipes de esta violenta toma del espacio por parte del gran capital. O sea, ¿cuál es el trabajo, la labor o cómo el arte o los artistas también son arma de servicio del gran capital para estos procesos de gentrificación? A mi me causa mucho ruido este tipo de proyectos donde quieren visibilizar voces. Para mi es más honesto hablar de cómo yo veo mi posición de productor visual dentro del entramado o dentro del gran complejo industrial de la cultura. Se me hace más honesto que tratar de hablar de los mismos desfavorecidos, pues, yo no podría.

G: Hay algo ahí que me interesaría abordar y es que, o sea, hay una parte dual que el arte puede ser una herramienta de protesta, pero al mismo tiempo esta herramienta parte de un privilegio como artista de tú poder decir algo, como de… No quiero decir responsabilidad, porque creo que no es responsabilidad, pero sí hay un posicionamiento como de «yo estoy facultado para decir algo», ¿no? ¿Qué opinas de esa contradicción constante?

O: Pues, justo señalando. En primera instancia, pues yo no soy un artista que goce de los privilegios de otros artistas, pero aún así, siento que es importante señalarlos. Tal vez si viviera directamente de mi producción artística, o me diera los placeres de la vida que la otra gente tiene, pues, tal vez mi trabajo sería de otra manera. Pero como no, pues digo, es necesario como problematizar al menos. Problematizar a ver qué pasa. Mucha de la característica del arte oaxaqueño, como Toledo, por ejemplo. En mi caso sí es necesario señalar dos cosas muy importantes dentro del proceso, no solo mío, sino de varios artistas de aquí de Oaxaca, que es cómo nos determinó, por ejemplo, políticamente el 2006, que fue un conflicto magisterial y popular en la ciudad de Oaxaca que modificó cuál era el posicionamiento de los artistas, dentro de ellos está Toledo. Toledo, al mismo tiempo que es un gran mito. Es como el Batman de Oaxaca, Chapuliman le decía un amigo; su figura al mismo tiempo jugaba dentro del complejo cultural. Por ejemplo, esta pieza que tiene de Los Cuadernos de la Mierda, que es una pieza que se la dio como pago en especie a la Secretaría de Hacienda, o sea, como que configuró unas piezas donde les decía: «yo les estoy pagando con mierda».

[Risas inaudibles de Uriel].

Omar: Yeah. And I needed the money, like always. When I gained it I said to myself: “well, it’s a good time to tell that”. Just that, you know? In that time, Peña Nieto was the president and I say: “I award to me the idea that I’m a governamental artist, regime’s artist”. And from it I was producing some ideas like making a political party. That was the idea. For example, I’d watch people who gained the same scholarship and say: “no, I’m still critical”, but they are living by the money regime gives to them. And you can say: “it is valid”. But, we can also question it.

Gerardo: Like a complex contradiction, isn’t it?

Omar: Yes. In my case, obviously… I need the money because lastly it’s necessary for people like me who produce art but not, hum, through galleries or patrons. So, it’s a valid income, very relevant for us. So, in that case, I said: “I will continue with that joke, in that way to me”. But, the idea is to question the link between government and artists. For example, in the rules of the scholarship say you have to put on your work the following sentence: “this project was supported by the scholarship Jovenes Creadores”. Always have to appear. So, I said to myself: “I put the logo of my mother’s business too”. Like a sponsor. It’s like a way to amuse myself.

O: Y eso para mi es como, justo, como que a mi lo que me interesa es entender las dinámicas internas del juego llamado «Arte Mexicano» y jugarlas y decir: «a ver qué pasa», ¿no? Jugarlas, ponerlas ahí sin tenerles este respeto, esta aura mística, a los objetos artísticos. Y decir: «la gente que produce arte, caga», y puede cometer errores y eso es justo lo que a mi me parece importante señalar respecto a tu pregunta, de que creo que es importante señalar que todos los artistas son personas que pueden cometer errores. Y por lo tanto decir que tienen responsabilidades sociales. Es como alguien que se dedica a la carpintería o a vender dulces, o a un empresario; pues también tienen responsabilidades sociales, sólo que a veces pareciera que a los artistas también se les exige, o se exigen a sí mismos, o nos exigimos a nosotros mismos ser «faros morales».

G: Sí, sí claro, entiendo completamente de qué va todo esto, porque al final no he visto yo que alguien saque a la superficie este tipo de cosas; uno que está dentro del medio lo nota, pero pues allá afuera la gente sí puede ver esa contradicción. Este wey está cobrando de acá, pero al mismo tiempo los está criticando, es un extraño.

O: Cuando recibí las dos becas que me han dado, siempre he dicho: «ah, ahorita es como con mis amigos». Por ejemplo, cuando me dieron la beca les dije: «todo este año que me dieron la beca, voy a votar por el PRI». Ahora, cuando me dieron la beca y estaba Andrés Manuel, dije: «Yo voy con la 4T».

U: ¿Cómo ves tú la escena del arte en Oaxaca?

O: Un maestro decía que Oaxaca es tan enredado que hasta el queso lo hacemos bola. [Risas]. Y estoy de acuerdo. Me imagino que así en varios lugares, pero uno como es oaxaqueño debe demostrar el poco nacionalismo que le queda.

G: Hace poco escuché a una persona que conozco, fue a comprar obra en Oaxaca o en Guanajuato, la verdad no me acuerdo. Pero el punto es que está curiosa esta historia porque compró arte supuestamente mexicano en una galería supuestamente mexicana, supuestamente, pero llegó a su casa a googlear al artista y resulta que era una morra francesa que vendía artesanías o arte inspirado en algo mexicano. Y creo que eso presenta esa dicotomía sobre todo en Oaxaca o en otros lugares, donde creo que hay gente con capital de otros países que se está apoderando de la escena o de los lugares de expresión en los que, pues, naturalmente tendría que estar algo local, ¿no? Como una apropiación de la cultura mexicana.

O: Es una situación muy compleja, como les decía, porque, curiosamente, Oaxaca… Porque autocitándome (que es como de lo peor que puedes hacer, pero me cito)… Tengo una pequeña pieza que menciona que… ¿Ven que hay una frase muy famosa sobre que el arte es un arma cargada de futuro?

U: La he escuchado, sí. Sale también en una película.

O: Es, creo, que de Bretton o de un surrealista, me parece. Y yo dije: «sí, pero más bien, como toda arma, depende de quién la carga, quién dispara». Puede ser alguien que está en situación de riesgo o un político que solamente lo hace por disfrutar. Con esta metáfora de en verdad el arte sí es un arma, pero quién disparó el gatillo, ¿no? Y yo creo que en este caso, en el caso oaxaqueño, muchas de las acciones que hizo Toledo, que fue como casi, con todo su esfuerzo, poner a Oaxaca como un centro cultural importante a la par de las grandes capitales de México, como lo es la CDMX, Guadalajara y Monterrey; la gran diferencia es que aquí no se movía tanto dinero o no se mueve tanto dinero como en estas tres ciudades, lo que hizo fue poner instituciones culturales. Y eso a partir del 2006 y del noventa, empezó configurándose poco a poco el entramado cultural oaxaqueño. Que por supuesto ha traído muchos beneficios, muchísimos. Ver por ejemplo aquí referencias como Cuauhtémoc Medina, Jan Hendrix. Referencias que han hecho que el arte oaxaqueño también tenga más exploración de arte-contemporánea más interesante que hace unos 20 años, pero, por ejemplo, al mismo tiempo eso ha traído consigo justo esta violenta gentrificación, que vemos con artistas que vienen, no sólo de la CDMX, vienen también de otros países, que al mismo tiempo claro que enriquecen la cultura y la vida oaxaqueña.

G: Hay un tema de identidad, ¿no? Ahí está muy marcado.

O: Claro que hay muchos artistas del D.F. que ocupan y explotan la idea de Oaxaca, ya no tan evidentemente folklórica, pero sí como con un sesgo, que se les identifique que están produciendo en Oaxaca. Jan Hendrix, por ejemplo, que tiene una serie que se llama Yagul que es sobre Oaxaca y pone a un espacio como Yagul dentro del ecosistema artístico y referencial, pero trae con ello a gente que tiene recursos y con ello le arrebata el espacio a los oaxaqueños. Por ejemplo, estaba leyendo una investigación que decía que el 70% del centro histórico de Oaxaca ya dejó de ser para vivienda y ahora es para comercio. Hay un cambio del uso de suelo.

G: Sobre todo porque este desplazamiento no sólo es cultural, ¿no? También es urbano y social en ese sentido, están desplazando a la gente residente y hay un proceso de neocolonización bastante intenso que empieza por lo cultural.

O: Sí, por lo cultural y como por el rediseño de las ciudades, por ejemplo, cómo renovaron esta parte de Regina y cómo con nosotros fue renovada esta parte del centro histórico. En nuestro caso, después del 2006, que fue un conflicto muy importante y bueno, el de ustedes fue ahí con Marcelo Ebrard. Estos espacios antes eran entendidos como la periferia o lugares como a los que no tenéis que ir, con la remodelación espacial ya cambia y ahora se vuelven centros de reuniones artísticas, culturales. Siempre hay que tener en duda estos discursos donde dicen que el arte por sí mismo, ayuda; tal vez no.

Gerardo: It’s very cool the way you formed it, the concept, the process, because it’s just a joke’s friend. I mean, it seems interesting to me because the way it began as a joke but at times it’s now a piece of art with a powerful concept, I think. It seems great to me. I think it requires much time and much effort.

Omar: Yes, of course. I feel it could be important because it was like saying: “ya, I gained it, and like too many people, I could flip my speech. People sometimes flip their speech by gaining it automatically. I just think I would think differently”. Before I gained that, I thought that things were made for the same artists who belong to the elite. Yes, it happens, but it’s questionable. All reactions between the State and how they coerce through subsidies. Let me say: “of course, we must question it”.

Uriel: In this case, for example, it gives you a smile while you talk about it, even though when you’re talking I can see your enthusiasm. It also caught our attention in a positive way, but, have you ever received a negative reaction from it?

Omar: I know many friends are not interested in that. They didn’t like it ‘cause it is so confrontative. I think it’s something I’ve thought about for many years: what’s an artist in the XXI century? Or, what are its implications in social framing? You know? For example, I got a piece that is named… It is something like a billboard that says: “they won’t pass”. It is a very famous phrase from the Spanish Civil War. It is similar to another piece I got that is named The artists are real estate agents, and it is about the gentrify’s process that happens in Oaxaca and the role of artists as part of the violence around public spaces’ appropriation. It is about capital, I mean. I think: what’s the true will between art and artists as a weapon of capital in this process of gentrification? It is complex. To me it is very rare and it seems so deep ‘cause there are a lot of art projects which tried to make visible outer works. For me it’s better and most honest to talk about my position as visual producer in this complex industry. It’s most sincere. I cannot talk about people who’re affected like them.

Gerardo: There’s something that I want to show. I mean, art can be a tool, in a way to protest, but it is also a tool that belongs to privilege and remarkable power roles. I do not want to say it’s our responsibility, but it is implicit that there exist positions around the role of artists as persons who can talk about whatever. However, it’s like: “hey, I’m empowered to think for you”, isn’t it? What do you think?

Omar: So, it’s just pointing at. At first, I am not an artist who enjoys the privilege like others, but I think it’s important to mark it. Maybe if I can live by my art productions or something, my work would be different. But, not. I say, I think it is necessary, to problematize at least. Most of Oaxaca’s art, like Toledo, for example, it’s about it. In my case, I tried to mark two things I consider important for my process. One of them could evoques the political conflict that happened in 2006 and ended and modified the way artists figure at that time, like Toledo. Toledo, at the same time, was a myth too. So, he’s like the Batman of Oaxaca; Chapulinman said a friend. For example, the piece The Notebooks of Shit, that is a piece he gave to Hacienda like paid, it configures a position: “I’m paying you with shit”.

U: Depende de donde lo mires, ¿no?

O: Sí, ¿a quién ayuda? A veces suena muy bonito cuando gobiernos, artistas y empresarios hablan que es importante la cultura o el arte para las comunidades. Igual y no. Tal vez hemos santificado demasiado el arte como para asumir esta carga de transformación cuando tal vez es todo lo contrario. Igual es una opinión controversial, ¿no?

Omar: And that’s for me, like, I am interesting in all of those things: comprehend the intern dynamics in this fuckin’ game we named mexican art. And play them and say: “let’s see what happens”. But without this mystic aura around art, around objects. I think it is important ponting at artists are people who can make mistakes and have some social responsibilities. Just like a businessman or a carpenter. It seems society demands us to be moral idols. Artists demand artists to be that.

Gerardo: Yes, of course, I understood it. Because, at last, it’s weird. A guy can be a regime’s employee and criticize the regime at the same time. It’s contradictorios, but it is the surface.

Omar: When I gained the scholarship I said: “ah, now I can be like my friends”. For example, I tell them: “all year I will vote for PRI”. This year I gained the scholarship again and I said: “I will follow 4T”.

Uriel: I want to ask you, how do you see the scene of art in Oaxaca?

Omar: A teacher used to say Oaxaca is so tangled that even the cheese we made it’s tangled. And I agree. I imagine it’s similar in other places, but here, ah, we must show the little feeling of nationalism we got.

Gerardo: Days ago I heard someone who bought a piece of art in Oaxaca, or Guanajuato, I dunno. The point is that this story is so curious ‘cause he bought Mexican art. Or it pretends to be Mexican art, you know? He was at home when he tried to search in Google, and when he was on it he realized the artist was not mexican but french, a french artist who made mexican art supposedly. And I think it represents a weird phenomenon: that dichotomy between Oaxaca and international-local culture. I mean, what’s Mexican art? I can portray appropriation from it.

Omar: That situation is complex, as I said before. But, curiously in Oaxaca… Because, auto-quoting me, I had a little piece that… Have you heard a famous phrase which talks about art as a weapon full of the future?

Uriel: Yes. I heard it. It comes from a movie.

Omar: I think it’s a Bretton phrase, I believe. And I said: “yes, but as a weapon it depends who is carrying it”. It could be someone who’s threatened or someone who is just enjoying themselves. With this metaphor it depends who is shooting, you know? And I think in that case, like too many actions Toledo made, it was about becoming Oaxaca into a cultural center like Mexico City or Guadalajara or Monterrey; the big difference is that here the economy is not too high like other cities. In 2006, in Oaxaca it started to configure a bit the networking around culture. It gives us so many benefits like Jan Hendrix or Cuauhtemoc Medina who are relevant references from Oaxacan art. But it also gave us a violent wave that contains remnants like gentrification and it came from artists too.

G: It’s about identity, isn’t it?

O: Well, there’re many artists from Mexico City who occupy and exploit the idea of Oaxaca as a folkloric thing, not so many, but it is like a bias, like identifying that they’re producing art here. Jan Hendrix, for example, he got a series named Yagul that is about Oaxaca and he put a space like Yagul into the artistic ground, but at the same time it brings us resources and grabs it from Oaxaca’s people. For example, I read a paper that talks about 70% of spaces in the center of Oaxaca are not more for living, now are for business.

G: Yes, because this shift is not only for the cultural landscape. It’s also urbanistic and social in that way. They are shifting people who lived there for years and now it’s a process like decolonization that is so intense and becoming from the cultural landscape.

G: En ese sentido crees que haya «buen arte» o «mal arte», o crees que hay arte cuando lo hay y no cuando no lo hay.

O: Hijole, yo considero que el arte funciona. Si funciona bien, si no, no. Por ejemplo, cuando no hay una relación entre objeto y discurso y lo que estás viendo. Porque eso de decirle «mal o buen arte», sí se me hace muy arriesgado, justo, ¿quién soy yo para elegirme juez?

G: Claro, sí, sí, sí. Cambiando un poquito de tema, hemos visto que también, además de esas producciones conceptuales, dibujas y haces otro tipo de proyectos, ¿cómo te relacionas tú con el dibujo? ¿Qué más haces aparte de eso?

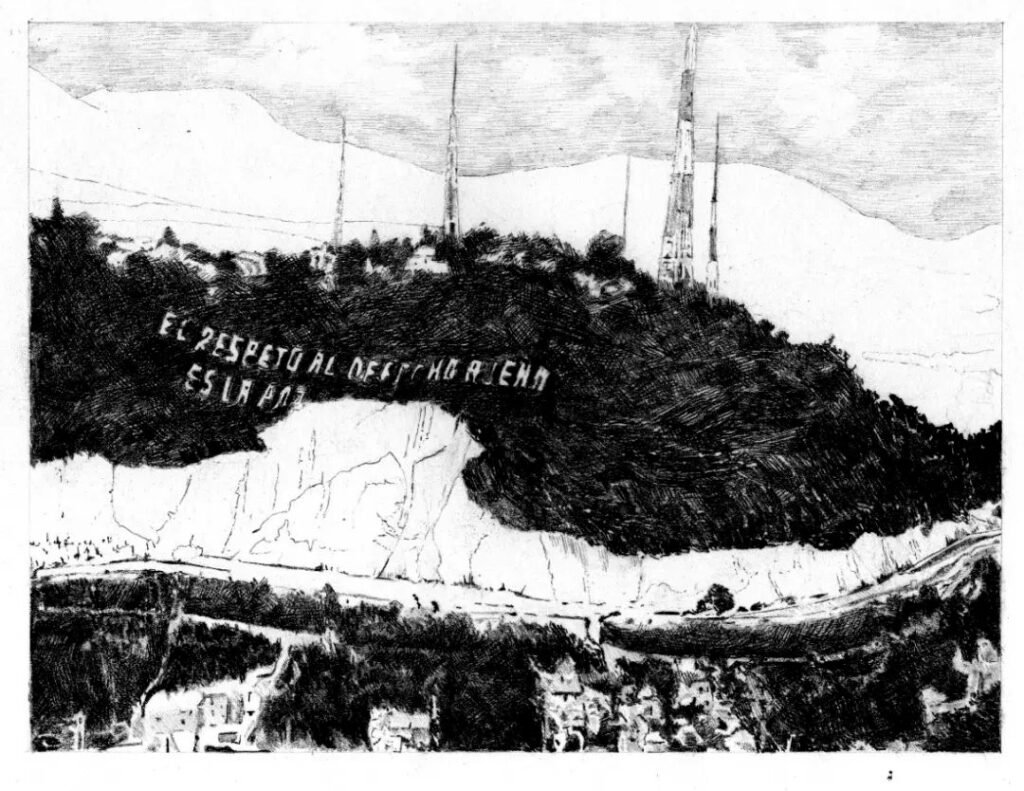

O: Creo que me faltó mencionar que yo me formé como grabador en metal, en la Facultad de Artes y Diseño de la UNAM, y ahí estuve trabajando gran parte de mi vida. En el grabado siempre me sentí muy identificado por varias cosas, por la materialidad de trabajar una placa de metal y por esta idea de la reproductividad de la imagen. De hecho, yo siempre he pensado que, aunque los proyectos que últimamente he tenido se relacionan más con el dibujo, en verdad lo estoy pensando desde el grabado.

O: Por ejemplo, formal, blancos y negros, contrastes, buscar lograr esos negros que te da el grabado a través del grafito, etcétera. Y en ese aspecto mi relación con el dibujo es una: la economía; soy alguien que piensa mucho en la economía de los materiales. O sea, con la pandemia. No sé si a ustedes les pasó, pero a mi me hizo replantearme cómo producir con lo esencial. Sólo tenía una mesa. Ahora por esas condiciones, tuve que salir de ese espacio por el recorte de personal.

U: Chale.

O: …Regresé a la casa de mis padres y solo tenía una mesa y aquí estaba mi computadora, lo que más cabía era una hoja tamaño tabloide y unos cuantos lápices, no tenía más. Y como que eso me cambió el chip: ya no estás en esta situación de tener un taller, de tener un espacio construido y determinado para solo producir, sino que ahora tienes que combinar trabajo, tu producción personal y dormir en el mismo espacio, ¿con qué produces? Y como que ahí me replantee las cosas. Ahí fue donde dije: «yo no vuelvo a producir obra que no quepa en un folder», porque ahorita estoy en casa de mis papás, pero no sé si me tenga que mover a otro lugar y a partir de ahí fue que decidí que sólo iba a producir tamaño carta. Que es un tamaño industrializado como ajeno a mí, ajeno a mis decisiones pues, que se hace con lo mínimo, con hojas tamaño carta y unos cuantos lápices, ¿cuál es su límite, no? Con esa reflexión empecé como otros a replantear cuál es mi relación con el espacio oaxaqueño.

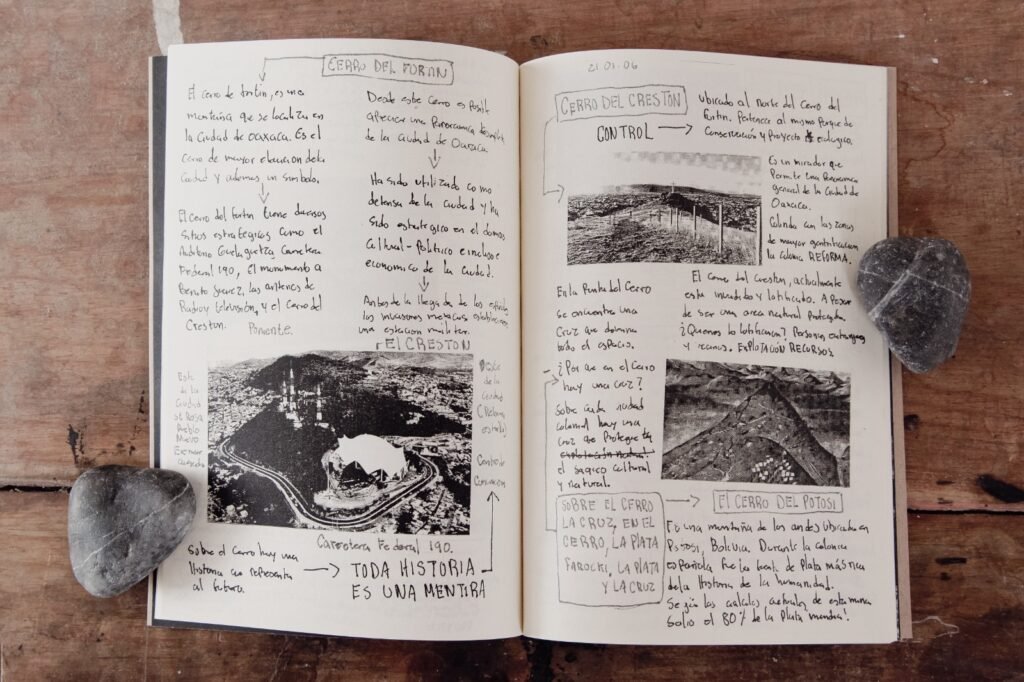

O: Antes lo veía estando en el D.F. con esta especie de nostalgia, de alguien que pues está allá, pero le gustaría estar en Oaxaca y extraña su casa, extraña a sus papás, extraña a sus amigos. Ya estando aquí en Oaxaca yo ya no puedo hablar de eso, porque ya estoy aquí y empecé a ver cómo mi trabajo tenía una reflexión sobre el paisaje. Creo que es inevitable que mi trabajo hable sobre el espacio. Y dije: «voy a hablar de lo que conozco, ya no quiero hablar de lo que no conozco y nunca he querido hablar de cosas que no son conocidas», entonces empecé a hablar sobre el Cerro de Fortín, que es este cerro que está aquí cerca de donde vivo y que ha sido como una referencia personal, muy personal, porque siempre he ido ahí con amigos, con mi familia, o a hacer ejercicio o sólo ir a caminar. Pero, también es un punto referencial importante dentro del ámbito cultural turístico oaxaqueño. Y pues empezar a trabajar con estos espacios que conozco. Sobre todo con este espacio que conozco más o menos bien, pues dije: «ya tengo las dos cosas con lo cual quiero hablar», con el material mínimo, con esta idea de ahorrar, espacio, tiempo y dinero; y hablar de un espacio conocido para mí. Y eso fue lo que me ha hecho sólo centrarme en hacer dibujo, pero, pues, por fortuna, conozco amigos que son muy buenas personas que me han invitado, por ejemplo, a hacer un librito, publicaciones en serigrafía, en grabado o, por ejemplo, hice una residencia aquí en el IAGO en donde pude también generar una especie de trípticos. Igual no sé si los estoy aburriendo.

G: No, no, no. Al contrario.

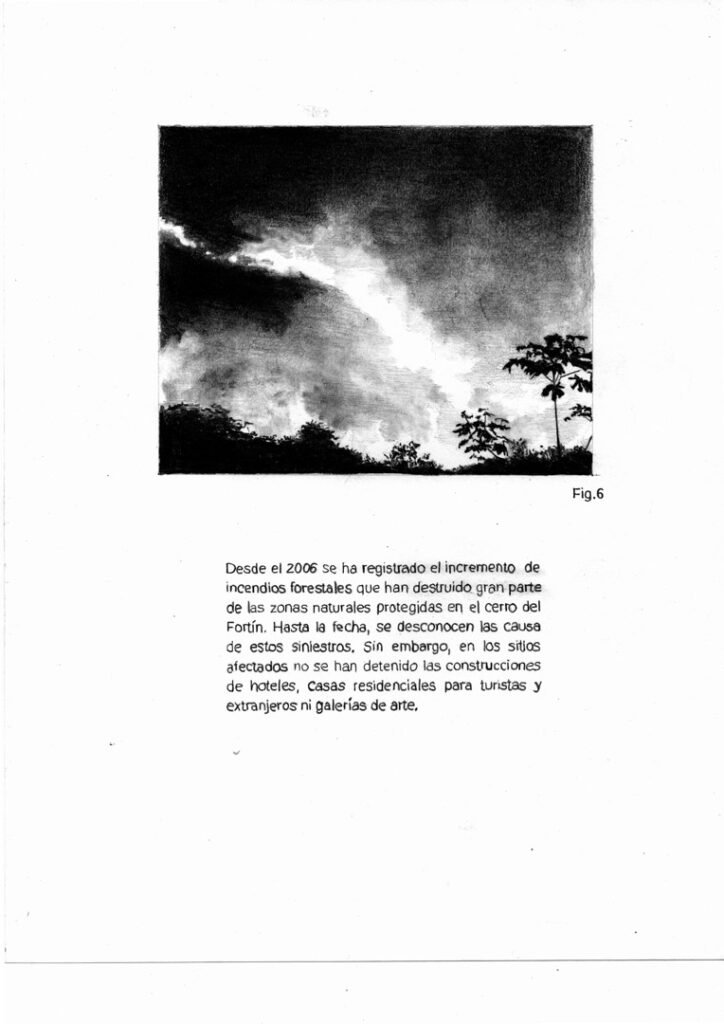

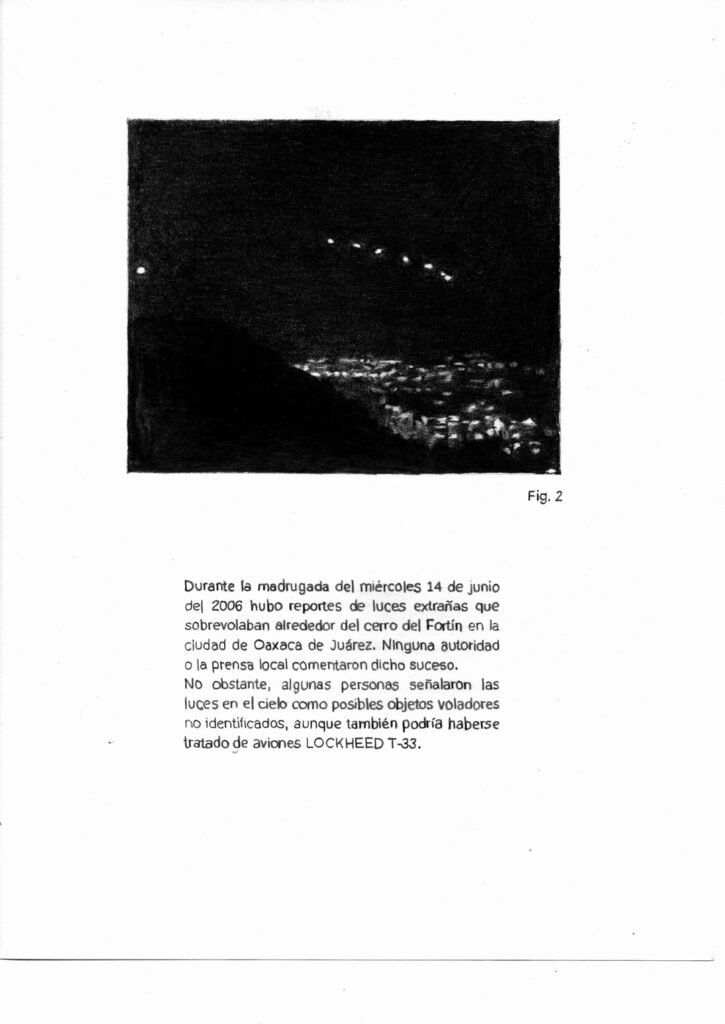

O: Estos como trípticos. Se llama Historia de un Cerro, donde a través de texto, que todo el texto es una impresión serigráfica, recupera tanto los relatos oficiales como los orales, pero también con mucha, mucha invención mía. Hay cosas donde yo estoy inventado completamente mi historia.

U: ¿Cómo es tu proceso creativo, por ejemplo, de esos dibujos? ¿Cómo lo empiezas, cómo lo concibes?

O: La verdad es que siento que es muy repetitivo e incluso hasta aburrido y mecánico. Si me ven dibujando van a decir: «este bato es el bato más aburrido que conocemos». En este caso sólo tenía la idea del tríptico, pues sólo fue pensar las imágenes, ver muchos trípticos, por ejemplo de estos guías de turistas, que es en lo que está basado esta pieza y parodiadas con el mismo lenguaje, con el mismo discurso y diciendo: «bueno, voy a proponer que esta pieza es un falso tríptico turístico sobre el Cerro de Fortín». Casi todo lo que hago son sólo chistes con mis amigos. Eso me gusta mucho. Hay unos dibujos que juegan con temáticas muy serias y de repente aparece como que un ovni, puede ser un helicóptero de la policía federal, como que justo es lo que el humor, la ironía, me permite hacer pasar una verdad como a través de un chiste. Yo a veces así lo pienso.

O: Yes, by the cultural and the redesigning cities plan, for example, the case of Regina at the center of Mexico City that was renewed. In our case, after 2006, that was a conflict so relevant, like yours with Marcelo Ebrard. These spaces that were built for peripheral people are now spaces for artists. I doubt that space because it says that helping people by itself but, maybe not.

U: It depends what perspective you got, doesn’t it?

O: Yes, it is like: who is helped? It sounds so pretty when the regime and artists and companies are talking about how relevant is culture and art for communities. Maybe not. Perhaps we made holy the meaning of art and assume that weight is like the soul of transforming when it’s opposite.

G: In that way, do you think there exists good art and bad art?

O: Uhhhh. I mean, I consider art to be art when it’s working. I mean, if it’s working or not. For example, when there exists a link between object and meaning and what you’re seeing. To say bad or good art is for me so risky, yeah, who am I to say something?

G: Of course, yeah, yeah, yes. But, changing a bit. We saw you got conceptual productions too. I mean, you draw and make more projects. I want to ask you how your relationship with drawing is.

O: I forgot to mention I was formed as an etcher, and I was working like for a while. At it… I was feeling like I identified myself by it, ‘cause materiality, the fact around working on a metal’s slab and the idea of reproducing an image. Instead, I always think that although projects I made recently could be linked to drawing I thought it really by etch. Like formal, B&W, contrast, all about looking for that kind of black that you can get by etch, etcetera. And, I guess it is like my relationship with drawing: about economics. Firstly, because I felt good when I made etchings, but mainly because I’m someone who’s always thinking about the economy of materialities. I mean, while pandemic. I dunno with yours but for me it was revealing I got to produce with the essence. And I got a desk while I got a big space before, you know? Now, because of too many conditions, I had to move.

O: So, I went back to my parents’ home and I just got a tiny desk and my computer, there is no more space, just for a ledger page, I guess, and other pencils. I had no more. And that was transforming myself into another kind of thought I could get: it’s no more time to produce bigger, so built pieces that can fit to the desk. I asked myself: which to produce? And I realized it. I said: “I will not produce pieces of art that don’t fit in a folder”. I have to move soon and I probably cannot move with everything I have. And it is interesting, making art that is in an industrialized size it’s like it’s unaffiliated. It is a thing that I wouldn’t choose. So, what’s its limit? With this thought I started to do more and more and I set out again every link from myself to the landscape here in Oaxaca.

O: I saw it before when I lived in Mexico City. This kind of nostalgia, I mean, of someone who is there but dreamt about being in Oaxaca, someone who’s missing its home and its friends. Here, it was kind of different. I cannot talk about it, so I think I started to think about landscape and make thoughts around it. I think it is inevitable that I talk about it. I said: “I will talk about something I knew, I do not want to talk about anything I didn’t know. And I have not talked about this kind of thing, so I started to talk about the Cerro de Fortín, which’s a mountain near where I live. It’s a place that’s also personal in a way, like good too. It is personal and familiar. I used to go there to run or meet people and it’s a place that’s also an important point in this cultural landscape. Then, I started to work on it, above all with these spaces which I knew very well. So, I told my friends something like: “I have two conditions where I can talk”. Firstly, that idea was about economics and materiality: about putting away money, and, secondly, about talking about Cerro de Fortín. So, it was making myself like paying attention, you know? By far, I met some friends who are great people and invited me, for example, to do something, like print a book, publishings with serigraphy or etching, or, for other hand, I made an art residence here in Yago where I could publish. I dunno if I’m boring for you.

G: No, no. No problem.

O: That publication was like a three part-document. Its name is Historias de un cerro and it’s like running through a text that is a text made by serigraphy and get back the official tales and my own interventions. There is a point where I am inventing the complete history. And I linked it with popular tales too. People said to me it seems so real. I dunno if it’s true but it seems to me like it’s not so extravagant. What I said is that here is also appearing the idea of the political party, the FONCA’s tagline and my business mom’s logo.

G: In that way, I want to ask you about your creative process. For example, how do you conceive your work as a draw?

O: I feel my work is so repetitive and even boring and automatic. If you see me drawing maybe you think: “that guy is so boring, he is the most boring man we met”. In the case of Historias de un cerro, I mean, it was only about thinking about the images and researching about three part-documents as well. My priority was like governmental and touristic guides. I want to talk in the same language. And I said: “well, I will put this info on a false three part-document, you know?”. Almost everything I made it’s like a joke within my friends. I like it. For example, there’s a drawing where UFOS play, it could be a police’s helicopter or something more. And it’s just humor, like joking. I think about it sometimes.

Uriel: Ha. Of course. But, when you’re drawing you are listening to music?

Omar: In the past, I used to listen to music like cumbia but it distracted me. It’s good music and cool, but I am trying to be so detallist and boring and automating. It was not for me. So, I decided to draw while doing boring things like Guanajuato’s cabildo’s sessions. Something random. I said: “ah, oj, I’m ready to draw or I am drawing” while that is happening.Therefore, I could listen to podcasts or sometimes Dragon Ball’s episodes. Yes.

Uriel: Ja. Claro. Pero… Mientras estás produciendo, mientras estás dibujando, ¿escuchas música? ¿Cómo es tu ambiente?

Omar: Antes solía escuchar música, mucha cumbia, pero me distraía. La cumbia es muy sabrosa, muy rica. Trato de ser muy detallado, muy aburrido, muy mecánico, y terminaba distrayendome. Así que decidí que para acompañar estos dibujos aburridos, tenía que poner cosas muy aburridas, y ponía sesiones del cabildo de Guanajuato, cosas así porque como no les pongo atención digo: «ah, ok, ya lo estoy dibujando». Ya después me puse a escuchar podcast o luego capítulos de Dragon Ball. Sí.

No sé para que publico, de todas formas no ves mis indirectas.